THANK YOU FOR DOWNLOADING

Learn More

If you would like to hear more from Orbitas, including updates on our analysis and resources, please subscribe here.

Author: Anthony Mansell

COVID-19 shows the strain governments face during an unexpected crisis and the knock-on impact this has on the sovereign debt ratings and ability to raise capital of those least able to weather the storm. This offers a preview for a decade where climate transitions intensify. Countries that are not prepared for both increasing climate impacts and the transition risks associated with the path to net-zero emissions are likely to suffer further shocks and increased difficulty in raising much-needed capital.

Understanding the macroeconomic impact of COVID-19, and the government response is instructive when looking at future climate transitions. The COVID-19 pandemic has depressed economic activity throughout the world. The IMF forecasts $9 trillion in lost output because of the crisis. Faced with cratering demand and rising unemployment, the reaction from most governments across developed economies and emerging markets has been to increase government spending, often through increased indebtedness.

Tropical countries are already suffering due to the crisis. The industry where this is most notable is tourism which plays a major role in many tropical country economies. According to the World Tourism Organisation, global tourism could decline by as much as 80% in 2020 because of health concerns and travel restrictions. Indonesia’s government projects a $10 billion shortfall of tourism revenue in 2020 (equating to around 1% of GDP) because of COVID-19. The government response has been to loosen fiscal policy with a $28 billion boost in government spending (total Indonesian government expenditure in 2018 was around $170 billion). This story is repeated across most tropical countries and is likely to remain for some time, with economic recovery likely to be protracted – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts a 3 percent decline in 2020 and no growth in 2021.

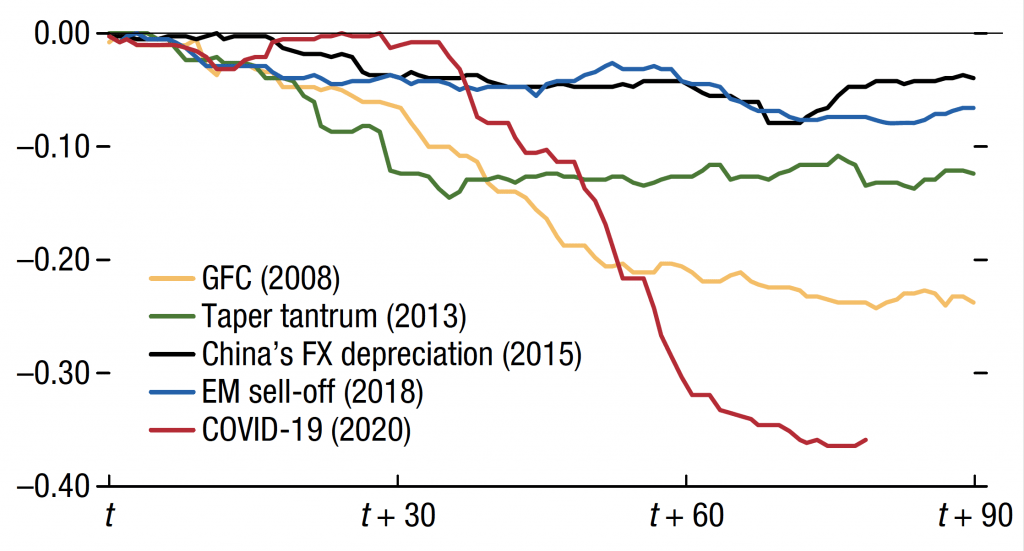

The consequences of this – increased government payables and a shortfall of receivables – matter for sovereign debt holders, for whom the risk of default is paramount. When the global economy falters, developing countries are particularly susceptible to debt crises. Investors take flight from assets perceived as risky to safe havens like U.S. treasury bonds. Growing risk aversion to emerging markets manifests through different channels, including foreign-based investors withdrawing their investments. Indeed, there has been a record pace of capital outflows from emerging markets since March (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cumulative Nonresident Portfolio Flows to Emerging Markets (Percent of GDP, based on daily observations)

Source: IMF Global Financial Stability Review, April 2020

These outflows shrink the capital available to companies and governments in these countries to finance investment and spending (e.g. public spending to provide fiscal stimulus) and service debt. The flow of foreign exchange also seizes up, as investors (or foreign visitors) are no longer converting dollars or euros into reals or rupiah. All other things being equal, this will cause a depreciation in the exchange rate. A declining exchange rate could impact the cost or even the ability to service foreign currency-denominated debt (typical in developing countries whose debt is held by international creditors). For example, only 19% of Indonesia’s external debt (held by creditors abroad) is denominated in Rupiah, meaning that the cost of debt service for the remaining 81% of external debt effectively rises as its currency depreciates.

The result is that the risk of a debt default or restructuring rises. Indeed, many emerging markets have already faced downgrades from sovereign debt rating agencies because of concerns about their debt stemming from COVID-19. Half of the countries the World Bank supports are either at risk of – or are already in – debt distress. The G20’s decision to suspend bilateral debt service for low- and middle-income country debt is a recognition that the economic crisis is making sovereign debt repayment challenging or impossible while the COVID pandemic persists.

How does this relate to climate transitions? This cartoon published as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold illustrates the basic logic – that a broader wave of climate risks loom on the horizon.

Credit: Statistically Insignificant (Instagram: @Statisticallycartoon)

The physical risks and transition pathways associated with climate change already affect economies throughout the world. Physical impacts are accelerating gradually, punctuated by major storms and extreme weather events. Climate transitions are underway, but are due to accelerate, including for commodities long associated with deforestation such as beef, palm oil and soy. Initial work by the Grantham Institute on sovereign debt and natural capital makes the case that the 2020s is the critical decade for climate transitions. The Inevitable Policy Response (IPR) scenario forecasts an “abrupt intensification” of climate policies in the early 2020s. This will further create disruptions.

Put simply, the 2030 economy will need to look very different from the 2020 economy. The challenge facing governments is to ensure transitions are smoother and well-managed, rather than sharp and dislocating.

For tropical commodities that are globally traded, climate transitions could present sovereign risks. The sudden decline in oil prices offers an instructive analogy, particularly given the link between the risk premium on sovereign debt and oil prices. The International Energy Agency forecasts a decline of 8.1 million barrels per day of oil demand in 2020, a record decline. This will have knock-on implications for government revenue in oil-producing nations.

Scenarios, where similar risks manifest for tropical commodities, are not difficult to imagine. A consumer revolt from beef towards vegetarian alternatives coupled with import restrictions on soy associated with deforestation would hamper two major Brazilian export industries. Soy alone has a positive trade balance of around $25 billion per year, according to UN COMTRADE, and accounts for over 10% of Brazil’s exports. The macroeconomic spillover within a country would be substantial, analogous to the vulnerability oil-producing countries face to a low-carbon transition away from fossil fuels. Holders of sovereign debt should, therefore, pay close attention to how climate risks, both physical and transition, will impact strategic national commodities such as beef, palm oil and soy. Insulating their holdings requires proactive consideration of climate risk and protection against portfolio losses.

COVID-19 and climate change pose distinct risks to sovereign debt, but the after-effects of COVID-19 will impact the capacity for governments to finance climate transitions. Taking emerging markets as a whole, total debt levels stand at around 170% of gross domestic product, a 54% increase since 2010. The economic downturn will push tropical governments to further expand fiscal and monetary policy to soften the blow.

This presents a dilemma for sovereign bond investors. Failure to invest in climate resiliency or reduce exposure to climate transitions risks the future macroeconomic health for tropical countries. For example, $20 trillion in investments to improve agricultural yields are needed globally by 2050, which requires major public investments in improving tropical commodity productivity. However, providing the financing necessary will become riskier if rising debts accumulated in the fight against COVID-19 make debt service too burdensome.

How should Sovereign bondholders react? Tropical commodities will continue to play an important role in the future economy. Therefore, the transition-resilient pathway is for sovereign debtholders to give fiscal space to tropical governments who structure their post-COVID recoveries in alignment with 1.5C or 2C scenarios. Even if governments are carrying a higher debt burden because of COVID-19, reforms and investments to align with a climate transition could realize value for investors by lowering exposure to transition risks. It raises the importance of forecasting how these risks could play out and factoring that into valuation decisions. Orbitas is developing scenario analysis specific to tropical commodities exactly to allow capital providers to understand how transitions will impact their holdings.

Public investments to align with a 1.5C or 2C transition pathway will reduce long-term sovereign risk. In addition to the fiscal costs being deployed to fight COVID-19, bondholders should encourage governments to invest in a “green recovery” that reduces transition risks. The rapid spread of COVID-19 took governments by surprise, and its impacts are being felt in government bond markets. There is more time to prepare economies for looming climate risks, but there is also no time to lose.